The project, with a $5 million grant from the US National Institutes of Health, aims to develop more individualised treatments for patients with Parkinson’s — the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s.

“We will try to understand how our brain controls the actions we perform, how we make decisions between competing goals, how we stop moving, and how we switch actions,” said Vasileios Christopoulos, assistant professor of bioengineering at University of California-Riverside.

The brain network associated with action regulation is disrupted with Parkinson’s, causing slower movements, difficulty stopping a movement, freezing, or having trouble initiating a new action.

As the disease progresses, dopamine-producing cells die. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter, responsible for feelings of pleasure which in turn fuel motivation.

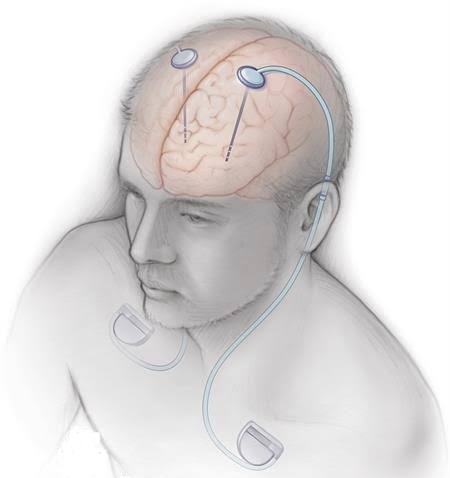

A first step in treatment is often L-Dopa, a drug meant to replace lost dopamine. When L-Dopa or similar medications stop working, deep-brain stimulation is often a last-ditch treatment. Electrodes are implanted to stimulate an area of the brain called the subthalamic nucleus or STN, which is involved with Tourette’s syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder as well as Parkinson’s.

“When a bus is coming and you want to stop crossing the street, the STN is involved. It’s the brake you have in your brain when you want to stop what you’re doing,” Christopoulos said.

“In Parkinson’s, we know this area is hyperactive. For them, every action is like driving a car with their foot on the brakes.”

For the project, around 200 patients will be awake while the electrodes are implanted.

They will play a video game with a joystick, before, during and after surgery, allowing the research team to see the effectiveness of the treatment in real time.

The patients’ behavioural and neurological data will also help Christopoulos build a large-scale mathematical model of the brain, so that theories about its function can be tested.

“As an outcome of this project, we hope to optimise treatments and make them patient specific,” Christopoulos said.

“We know Parkinson’s is a terminal disease, but we want to give people a better quality of life, and a longer life.”

–IANS

rvt/pgh